frobles@MiamiHerald.com

U.S. archaeologist Nathan Mountjoy sits next to stones etched with ancient petroglyphs and graves that reveal unusual burial methods in Ponce, Puerto Rico. The archaeological find, one of the best-preserved pre-Columbian sites found in the Caribbean, form a large plaza measuring some 130 feet by 160 feet that could have been used for ball games or ceremonial rites, officials said.

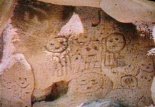

U.S. archaeologist Nathan Mountjoy sits next to stones etched with ancient petroglyphs and graves that reveal unusual burial methods in Ponce, Puerto Rico. The archaeological find, one of the best-preserved pre-Columbian sites found in the Caribbean, form a large plaza measuring some 130 feet by 160 feet that could have been used for ball games or ceremonial rites, officials said.SAN JUAN -- The lady carved on the ancient rock is squatting, with frog-like legs sticking out to each side. Her decapitated head is dangling to the right.

That's how she had been, perfectly preserved, for up to 800 years, until the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers came upon her last year while building a $375 million dam to control flooding in southern Puerto Rico.

She was buried again last week with the hope that some day specialists will study her and Puerto Rican children will visit and learn about the lives of the Taino Indians who created her. But archaeologists and government officials first had to settle a raging debate about who should have control over her and other artifacts sent to Georgia for analysis.

The ancient petroglyph of the woman was found on a five-acre site in Jácana, a spot along the Portugues River in the city of Ponce, on Puerto Rico's southern coast. Among the largest and most significant ever unearthed in the Caribbean, archaeologists said, the site includes plazas used for ceremony or sport, a burial ground, residences and a midden mound -- a pile of ritual trash.

The finding sheds new light on the lifestyle and activities of a people extinct for nearly 500 years.

Experts say the site -- parts of it unearthed from six feet of soil -- had been used at least twice, the first time by pre-Taino peoples as far back as 600 AD, then again by the Tainos sometime between 1200 and 1500 AD.

''It was thrilling, a once-in-a-lifetime thing,'' said David McCullough, an Army Corps archaeologist. ``Just amazing.''

But like all things on this politically charged island, the discovery got caught up in a sovereignty debate: If an archaeological site rich in historic and cultural value is discovered in a federal construction site in Puerto Rico, a commonwealth of the United States, who should be in charge of it?

After months of finger-pointing and accusations of officially sanctioned plundering, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers poured $2 million into preserving the site. Plans to put a rock dump over it were changed, and the unearthed discovery was reburied with the aspiration that archaeologists will eventually return to dedicate the 10 or 20 years needed to thoroughly study the finding.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers promises the collection sent to Georgia will be returned to Puerto Rico. Some 75 boxes of skeletons, ceramics, small petroglyphs and rocks were sent via Federal Express in two double-boxed shipments for analysis.

''The site is a significant contribution to our understanding of what Indians were doing,'' McCullough said. ``The thing that makes it unique is that the petroglyphs are so finely done. We originally were supposed to be there six weeks. It wound up taking four months.''

McCullough said the corps had an inkling that the site was there since the mid 1980s but had never done much testing. They started digging in earnest last year while building a dam and lake to protect the region from floods, and realized the site had significant value.

The corps found a ball court with four walls lined by tall stones, where they believe the Tainos either danced or played games. Three were covered in petroglyphs, among the best experts had ever seen. Some of the figures were carved upside down, which none of the archaeologists had ever seen before. Discoveries included a jade-colored amulet and the remains of a guinea pig, likely the feast of a tribal chief.

''The size of the ball court is bigger than just about anything else in the Caribbean,'' McCullough said.

Archaeologists believe as many as 400 people are buried there.

But in its quest to build the dam and use the location as a dumping ground for rocks, critics say the corps quickly hired a private archaeological firm to mitigate -- a hurried process of saving what can be conserved so a project can go forward. The company sent 125 cubic feet of artifacts in two shipments to its facility in Georgia for analysis, a move allegedly made without consulting Puerto Rican authorities, which locals felt violated the law.

But the question became: Whose law applied? U.S. law says such artifacts found by the corps must be warehoused in a federally approved curating facility. No such place exists in Puerto Rico. And Puerto Rican law says historical artifacts belong to the people of Puerto Rico.

''In Puerto Rico, everything that has to do with our past is sentimental, and Puerto Ricans take it to heart,'' said Marisol Rodríguez, an archaeologist at the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture. ``There's a feeling that you're taking something that's mine. It's about our national identity, regardless of the island's political status.''

Rodríguez is pleased that the site has been preserved but acknowledges she was furious at how it was originally excavated with heavy machinery.

''I was so angry. I was indignant,'' she said. ``I could not believe that a place of such importance was being treated with such disrespect.''

New South Associates, the firm hired to do the digging, says it excavated about 5 percent of the site for study.

''It was in the newspaper that we raped and pillaged the site, because it all got caught up in local politics,'' said archaeologist Chris Espenshade, New South's lead investigator on the project. ``We are required to take the artifacts to a federally approved curating facility. That played into the idea that we were stealing Puerto Rican cultural patrimony away and never bringing it back. There's no question these things should be available for Puerto Rican scholars without them having to travel to go see it.

``It's a bad situation.''

What's left of the site will remain beside a five-year dam construction project, which will continue as planned. It may be vulnerable to floods, archaeologists acknowledged, but they note that it lasted that way underground for hundreds of years.

''It's not the best way to preserve it, but it's better than the alternative: to destroy it,'' Espenshade said. ``The Corps could have destroyed it, but they took the highly unusual step to preserve it.''

Puerto Rican authorities say they are committed to opening a facility needed to properly store and exhibit the artifacts.

The Institute of Puerto Rican Culture is scouting locations and trying to secure the approximately $570,000 a year needed to operate such a warehouse. Officials hope it will open as early as mid-2009, but some experts still worry.

''Nobody could believe that in the 21st century, a federal agency would hire a private agency to dig up a site and take things,'' said Miguel Rodríguez, an archaeologist who sat on Puerto Rico's government archaeological council for a total of eight years.

He quit in January following a heart attack, which he blamed on stress over the Jácana site.

''Those are the things that happened in the 18th and 19th century, not now,'' Rodríguez said. ``Nobody dares go to Mexico, do an excavation and just take the stuff. That's officially sanctioned looting.''

While officials debate where they will find the funds for a museum, storage facility and lab, the Department of Natural Resources has hired 24-hour security to watch over the archaeological site, just to be sure no artifacts wind up for sale on the Internet.

''With the artifacts in Georgia,'' Department of Natural Resources Secretary Javier Vélez said, ``at least they are not on eBay.''

That's how she had been, perfectly preserved, for up to 800 years, until the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers came upon her last year while building a $375 million dam to control flooding in southern Puerto Rico.

She was buried again last week with the hope that some day specialists will study her and Puerto Rican children will visit and learn about the lives of the Taino Indians who created her. But archaeologists and government officials first had to settle a raging debate about who should have control over her and other artifacts sent to Georgia for analysis.

The ancient petroglyph of the woman was found on a five-acre site in Jácana, a spot along the Portugues River in the city of Ponce, on Puerto Rico's southern coast. Among the largest and most significant ever unearthed in the Caribbean, archaeologists said, the site includes plazas used for ceremony or sport, a burial ground, residences and a midden mound -- a pile of ritual trash.

The finding sheds new light on the lifestyle and activities of a people extinct for nearly 500 years.

Experts say the site -- parts of it unearthed from six feet of soil -- had been used at least twice, the first time by pre-Taino peoples as far back as 600 AD, then again by the Tainos sometime between 1200 and 1500 AD.

''It was thrilling, a once-in-a-lifetime thing,'' said David McCullough, an Army Corps archaeologist. ``Just amazing.''

But like all things on this politically charged island, the discovery got caught up in a sovereignty debate: If an archaeological site rich in historic and cultural value is discovered in a federal construction site in Puerto Rico, a commonwealth of the United States, who should be in charge of it?

After months of finger-pointing and accusations of officially sanctioned plundering, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers poured $2 million into preserving the site. Plans to put a rock dump over it were changed, and the unearthed discovery was reburied with the aspiration that archaeologists will eventually return to dedicate the 10 or 20 years needed to thoroughly study the finding.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers promises the collection sent to Georgia will be returned to Puerto Rico. Some 75 boxes of skeletons, ceramics, small petroglyphs and rocks were sent via Federal Express in two double-boxed shipments for analysis.

''The site is a significant contribution to our understanding of what Indians were doing,'' McCullough said. ``The thing that makes it unique is that the petroglyphs are so finely done. We originally were supposed to be there six weeks. It wound up taking four months.''

McCullough said the corps had an inkling that the site was there since the mid 1980s but had never done much testing. They started digging in earnest last year while building a dam and lake to protect the region from floods, and realized the site had significant value.

The corps found a ball court with four walls lined by tall stones, where they believe the Tainos either danced or played games. Three were covered in petroglyphs, among the best experts had ever seen. Some of the figures were carved upside down, which none of the archaeologists had ever seen before. Discoveries included a jade-colored amulet and the remains of a guinea pig, likely the feast of a tribal chief.

''The size of the ball court is bigger than just about anything else in the Caribbean,'' McCullough said.

Archaeologists believe as many as 400 people are buried there.

But in its quest to build the dam and use the location as a dumping ground for rocks, critics say the corps quickly hired a private archaeological firm to mitigate -- a hurried process of saving what can be conserved so a project can go forward. The company sent 125 cubic feet of artifacts in two shipments to its facility in Georgia for analysis, a move allegedly made without consulting Puerto Rican authorities, which locals felt violated the law.

But the question became: Whose law applied? U.S. law says such artifacts found by the corps must be warehoused in a federally approved curating facility. No such place exists in Puerto Rico. And Puerto Rican law says historical artifacts belong to the people of Puerto Rico.

''In Puerto Rico, everything that has to do with our past is sentimental, and Puerto Ricans take it to heart,'' said Marisol Rodríguez, an archaeologist at the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture. ``There's a feeling that you're taking something that's mine. It's about our national identity, regardless of the island's political status.''

Rodríguez is pleased that the site has been preserved but acknowledges she was furious at how it was originally excavated with heavy machinery.

''I was so angry. I was indignant,'' she said. ``I could not believe that a place of such importance was being treated with such disrespect.''

New South Associates, the firm hired to do the digging, says it excavated about 5 percent of the site for study.

''It was in the newspaper that we raped and pillaged the site, because it all got caught up in local politics,'' said archaeologist Chris Espenshade, New South's lead investigator on the project. ``We are required to take the artifacts to a federally approved curating facility. That played into the idea that we were stealing Puerto Rican cultural patrimony away and never bringing it back. There's no question these things should be available for Puerto Rican scholars without them having to travel to go see it.

``It's a bad situation.''

What's left of the site will remain beside a five-year dam construction project, which will continue as planned. It may be vulnerable to floods, archaeologists acknowledged, but they note that it lasted that way underground for hundreds of years.

''It's not the best way to preserve it, but it's better than the alternative: to destroy it,'' Espenshade said. ``The Corps could have destroyed it, but they took the highly unusual step to preserve it.''

Puerto Rican authorities say they are committed to opening a facility needed to properly store and exhibit the artifacts.

The Institute of Puerto Rican Culture is scouting locations and trying to secure the approximately $570,000 a year needed to operate such a warehouse. Officials hope it will open as early as mid-2009, but some experts still worry.

''Nobody could believe that in the 21st century, a federal agency would hire a private agency to dig up a site and take things,'' said Miguel Rodríguez, an archaeologist who sat on Puerto Rico's government archaeological council for a total of eight years.

He quit in January following a heart attack, which he blamed on stress over the Jácana site.

''Those are the things that happened in the 18th and 19th century, not now,'' Rodríguez said. ``Nobody dares go to Mexico, do an excavation and just take the stuff. That's officially sanctioned looting.''

While officials debate where they will find the funds for a museum, storage facility and lab, the Department of Natural Resources has hired 24-hour security to watch over the archaeological site, just to be sure no artifacts wind up for sale on the Internet.

''With the artifacts in Georgia,'' Department of Natural Resources Secretary Javier Vélez said, ``at least they are not on eBay.''

Source: Miami Herald

No comments:

Post a Comment