by Roberto Múcaro Borrero (Taíno)

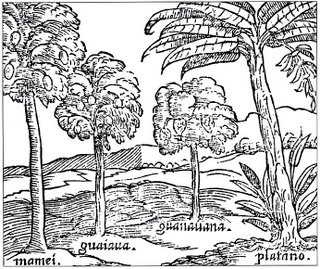

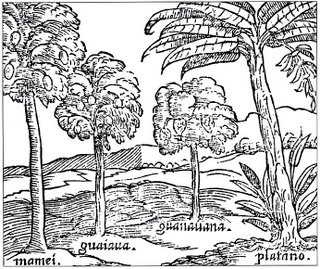

Early examples of the ancient Caribbean pharmacopoeia

Early examples of the ancient Caribbean pharmacopoeia

In recent years, interest in phytotherapy or the use of traditional herbs, herbal remedies and medicinal plants has continued to gain momentum. According to analysts, this interest has been increasingly stimulated by the rising cost of prescription drugs and transnational bio-prospecting for the development of plant derived drugs (applicably termed “the new gold rush”). While the social and economic implications of this trend merit attention, increased financial investments and current research seem to indicate that medicinal plants will continue to play an important role as a “re-emerging health aid”.

As the use of medicinal plants and the practice of traditional medicine is the norm for significant portions of populations in many so-called “developing countries”, this paper will take a closer look at the development, usage and legacy of medicinal plants, and their particular relationship to Indigenous Peoples in the Americas. Further, it should be of no surprise to the reader that coinciding with the increased attention on medicinal plants, the “global community” has also been witness to an increased focus on the world’s Indigenous Peoples.

Indeed, the 1992 United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) recognizes the “close and traditional dependence of many indigenous and local communities embodying traditional lifestyles on biological resources” and that governments “subject to national legislation, respect, preserve, and maintain knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities embodying traditional lifestyles relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity”. The CBD also recommends the “approval and involvement of the holders of such knowledge, innovations and practices” and encourages “the equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the utilization of such knowledge, innovations, and practices”.

As the United Nations is considered an international standard setting body, this recognition is an extremely important development as industrialized societies continue to exploit medicinal plants, developing drugs and chemotherapeutics not only from these plants but also from herbal remedies traditionally used by rural/local communities and Indigenous Peoples. Today, because of the ever-increasing cost of health care and public demand, there is a great risk that many medicinal plants have already become or face extinction and/or a loss of genetic diversity’.

As the patenting of life forms, and genetic research/engineering have also become increasingly relevant factors in this field, another international organization, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) has begun to research and analyze the implications of these developments under the intellectual property system via the headings “traditional knowledge and folklore”.

Medicine: A Concept or Product?Using a wide range of disciplines and resources (archeology, ancient text, anthropology, linguistics, etc.), scientist have ‘confirmed’ that plants have been used as a source of medicine in virtually all cultures. The widespread use of traditional herbs and plants reveals the medicinal properties inherent in many natural products.

It is generally accepted that medicine is linked to health, and the World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as a “state of complete physical, mental, and social well being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. As an indigenous person I would also include the idea of “spiritual well being” as the sum total of the various states of “being” identified by the WHO.

Traditionally, for many Indigenous Peoples the concept of medicine was and is still not as compartmentalized as generally practiced and promoted by Western society today. Indigenous communities throughout the world recognized the sacredness and all encompassing scope of the concept of medicine and this is historically demonstrated by the way of life of communities and individuals; especially with regard to interaction with and respect for the natural world. It is interesting to note that “Western” medical systems of today, which developed via the “man conquers nature” attitude now seem to promote a market driven philosophy of “specialized and prolonged treatment”.

In contrast, indigenous medicine was developed with the understanding that all things are interrelated and co-dependant and this worldview promoted the practice of “holistic prevention and cure”. This fundamental difference between Western philosophy and traditional indigenous worldview offers an important insight into not only why these traditional practices have remained even till today but also why they are now sought after by other sectors of the global community.

The Columbian ExchangeFor quite a number of “developing” countries in the Americas, medicine based on local tradition is still a main stay of health care. Within this context, the development, use and legacy of medicinal plants and herbal remedies has an historic and fundamental relationship with “American Indians”. From at least the 15th century, the use of medicinal plants (and food crops) has been consistently documented in the Western Hemisphere, even as many of the cultures responsible for these innovations have disintegrated or in some cases disappeared.

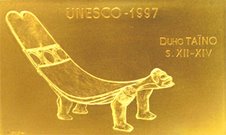

It is estimated that Amerindians developed 60% of the world’s food crops and there are no food plants native to the Americas that were not first cultivated by Indigenous Peoples of the region. As my own Taíno ancestors, and their close relatives the socalled “Carib”, were the first peoples in the Western Hemisphere to be called “Indians”, it must also be acknowledged that many of the medicinal plants and food crops that are now staples in Europe, Africa and Asia, were first encountered in the 15th century Caribbean. The Caribbean’s tropical environment was a virtual “pharmacopoeia” of medicinal plants and herbal remedies and the use of these important resources were not only accessed by so-called “Shamans/Medicine Women or Men” but by most members of the community.

Many Caribbean indigenous plants now identified solely as food crops were also valued by my ancestors for their medicinal properties. That I have included food crops as medicinal plants again speaks to the overall concept of medicine that Indigenous Peoples throughout the Americas observed.

Further, while scholars debate on the effects of introduced foreign diseases, medicine, and religion on the Indigenous Peoples of the Western Hemisphere, we can be sure that pre-Euro-contact lifestyle was a healthier one and a place where diabetes, high blood pressure, asthma, lung cancer, and AIDS were not a part of the peoples’ consciousness.

Just a few of the food crops and medical plants that my ancestors and relatives throughout the hemisphere developed, used and contributed to the world community include:

maisi (maize/corn); white potatoes; sweet potatoes; manioc (yuca/cassava);

mani (peanuts), chili peppers; cashews; tomatoes; okra; squash (including pumpkin);

yayama (pineapples);

bija or achiote (Bixa orellan); papaya; avocado (aguacate); kidney beans; lima beans; black-eyed peas; wild rice; blueberries; strawberries; pecans; quinoa; maple syrup; vanilla; cacao (chocolate); mint; aloe; ginger; and sage.

Indigenous Peoples of the Americas have also cultivated non-food crops such as cotton, sisal, indigo, basalms, latex (rubber), and chicle (chewing gum). Even some non-food crops that have a negative connotation today like tobacco and coca were used for spiritual and medicinal purposes. For example, tobacco was not only smoked but also used to cure aliments of the stomach, induce vomiting, and to treat snakebites, etc.

Early Woodcut of Caribbean Indigenous Tobacco Use. Tobacco is a Taino word.

Early Woodcut of Caribbean Indigenous Tobacco Use. Tobacco is a Taino word.

Coca leaves have been used by South American Indigenous Peoples for thousands of years, yet they are now the center of the “Drug Wars” as a result of their exploitation by non-indigenous people. Some of the traditional medicinal use of the coca leaves (which were chewed or ingested as a tea) included relief of hunger and fatigue, altitude sickness, increased respiratory capacity, cerebral and muscle stimulant, as well as relief of nausea and pains of the stomach without upsetting digestion.

As for food crops, fruits, and plants which were and are still harvested in the Caribbean region, just a few examples of medicinal uses include the wild sage (Lantana camara) used in tea to treat colds and chills, soursop or

guanabana (Annona muricata L.) used as a sedative for children, the

jobo (hog plum or golden apple) used to stop diarrhea or dysentery, and the silk cotton tree or

ceiba/kapok (Ceiba pentandra) used in baths to relieve fatigue and to counteract certain poisoning. Allspice (Pimenta dioica) was used not only to preserve meat and fish but also as a remedy to promote digestion, toothache relief, and the alleviation of muscle pain. Aromatic allspice berries have a long history in Caribbean “folk healing”.

In Jamaica, people drink hot allspice tea for colds, menstrual cramps and upset stomach. Some Costa Ricans use it to treat indigestion, flatulence and diabetes while it is considered a refreshing tonic in parts of Cuba. Guatemalans apply the crushed berries to bruises, joints and muscle pains. Culantro or Recao (Eryngium foetidum L., Apiaceae), not to be confused with its close relative cilantro (Coriandrum sativum L.), was use to treat fevers and chills, vomiting, diarrhea, and in Jamaica for colds and convulsions in children. The leaves and roots of culantro are boiled and the “tea” ingested to treat pneumonia, flu, diabetes, constipation, and malaria fever.

Many of these traditional indigenous practices continued to be observed today especially within the rural and urban populations of Caribbean society. As in earlier times, access to this traditional knowledge is not limited to “local specialist” sometimes called “Curandera/os” but to various members of the community.

Today, one of the most notable contemporary examples of the popular use of traditional medicinal practices in the Caribbean is the use and prominence of “Green Medicine” in Cuba. This practice has been a main stay in heath care for decades in this country and includes traditional indigenous plant and herbal remedies as well as alternative and holistic healing methods.

Another example of the prominence that traditional indigenous based medicine has attained in the Circum-Caribbean region is that in 1993, the Belizean government established the world’s first medicinal plant reserve. This 6,000-acre reserve, dedicated to the preservation of potential lifesaving herbs, is called the Terra Nova Medicinal Plant Reserve. Seedling plants rescued from rainforest areas in danger of destruction due to “development” are sent to Terra Nova for transplanting. The Belize Association of Traditional Healers runs this reserve.

As we move from the Caribbean islands on through the Americas, the importance of the tropical rainforest of South America in the discussion of medicinal plants and traditional healing practices must be acknowledged.

It is estimated that 90% of the rainforest flora used by Amazonian Indians as medicines have still not been examined by modern science. This situation represents a horrible irony as these unique ecosystems, which have been developed over millennia with the direct influence of Indigenous Peoples, are now disappearing at an alarming rate and the potentially catastrophic implications of this trend on the rest world are staggering. Further, this scenario is true not only of rainforest in the Americas but around the entire world. Of the few rainforest plants that have been studied by modern medicine, treatments have already been found for childhood leukemia, breast cancer, high blood pressure, asthma, and scores of other illnesses.

Indeed, 70% of the plant species identified by the US National Cancer Institute as holding anti-cancer properties come from the rain forest and an estimated 37% of all medicines prescribed in the U.S. have active ingredients derived from rainforest flora.

As we move into North America, an incredible amount of plant-derived medications have been identified in Mexico alone. Before contact with Europeans, the Maya and Aztec peoples kept many written records of the uses of medicinal plants in books that are now know as Codices. In the 16th Century many of these ancient text books of knowledge were literally burned by zealous Christian clerics who linked traditional indigenous knowledge to alleged “idolatry” and other so-called “pagan practices”.

The potential loss of that wealth of information is incomprehensible, and represents another one of the countless tragedies, which occurred as a result of these early forms of religious intolerance, xenophobia and racism promoted by the early Europeans colonist. Perhaps, as Walter R. Echo-Hawk contends “it is difficult for a culture with an inherent fear of ‘wilderness’ and a fundamental belief in the ‘religious domination’ of humans over animals to envision that certain aspects of nature can be sacred.”

Among the diverse communities of Indigenous Peoples who lived throughout the lands that are known today as the United States and Canada, the development, usage and contributions of medicinal plants are similarly as substantial and significant.

Just a few medicinal plants used by “Native Americans” included yarrow (for headaches), echinacea, golden seal, wild sarsaparilla (for blood, and sores), mugwort (dysentery), wormwood (sprains), bearberry (headaches), wild ginger (indigestion), common milkweed (diseases of women), and prairie sage (convulsions, hemorrhage, and tonic). American Indians were even using the dandelion long before the discovery of America for a wide variety of ailments. The plant was a sort of panacea (cure for everything) and recent scientific evidence exists to substantiate these uses.

Native Americans also used bearberry, or

kinnikinnick as they called it, in their ceremonial pipe in place of tobacco. The Arikaras cultivated sacred tobacco and mixed it with dried bearberry leaves and the dried inner bark of red dogwood. Some Native American tribes even mixed tobacco with bearberry to make a milder smoke. The use of tobacco and the smoking of the sacred pipe throughout the Americas cannot be seen in isolation from the use of other medicinal herbs like sage, cedar, black berry, and so many others, which were at times either chewed, brewed in teas or used as poultices.

A Matter of Respect

Like the sacred pipe, and even the ceremonial use of cigars, socalled “hallucinogens” have been part of the health and spiritual well-being of indigenous communities throughout the Americas for thousands of years. Even today, the sacramental use of sacred medicine plants like

ayahuasca,

peyote (Lophophora williamsii),

cohoba/yopo (Piptadenia peregrina/Anadenanthera peregrina), certain mushrooms and others are still well respected by those Indigenous Peoples who interact with these “holistic purgatives” on a regular basis. However, misunderstanding, abuse and exploitation of these sacred plants by non-indigenous people highlight other fundamental differences between Western and indigenous concepts of traditional medicine.

Indeed, it is important to again acknowledge the all-encompassing/holistic concept of traditional medicine for Indigenous Peoples and link this to the ideal of spiritual health as a primary goal for the community. With this in mind, Indigenous Peoples in the Americas have revered and used natural “hallucinogens” for their healing, cleansing and transformative properties “since time beginning”.

While modern science is just beginning to recognize, explore and even “validate” some of these traditional views, through the centuries writers have continually commented on the advanced medical systems of many South and North American Indigenous Peoples. Some writers have even acknowledged that indigenous medical traditions in the Americas were actually more advanced than those being practiced in Europe at the time of the Conquest.

In fact, while Europeans were still “bleeding” people to treat aliments, the so-called “red savages” of the Americas were in comparison leading much healthier lives and even performing complex medical procedures like brain operations, c-sections, setting bones, and using anesthetics etc. All of these traditional medical procedures were used in conjunction with medicinal plants, other natural resources and socio-religious ceremonies, which were and still are respected and considered sacred by many Indigenous Peoples.

To emphasize the similarity of Indigenous Peoples philosophy with regard to the sacred in all these processes, I will return my focus to the Caribbean where the Taíno Indian descendants in rural areas still honor tobacco as a sacred herb. Even before other herbs are picked for special teas or “un cocimiento”, tobacco seeds are used as an offering to the medicinal plants.

As one can see the popular phrase, “you are what you eat” was something my ancestors and their relatives throughout the Hemisphere were very familiar with and this is an ideal that is today worthy of attention and respect. As my community and other communities around the world are falling victim to diseases such as diabetes, obesity, high bold pressure, high cholesterol etc. as well as being enticed, coerced or unknowingly introduced to genetically modified foods, traditional knowledge is not only worthy of attention but it is a literally a matter of life and death.

But as with all aspects of life, the use of medicinal plants is ultimately a matter of respect for as the Taíno Grandmothers say the “plants know and can help you or hurt you, depending on how you approach them”.

*This article was published by the International Center for Cultural Studies and presented at the First International Conference & Gathering of Elders held 4-9 February 2003, in Mumbai, India.