The Effect of Indigenous National Parks in Modern History

|

The Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Center in Utuado is one of the Caribbean's most important Taíno archeological sites. |

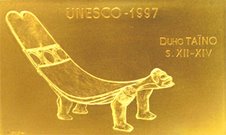

Artifacts created by Indigenous Peoples are an essential part of any basic archaeological research necessary for sociocultural and historic reattachment. In this modern era, there is incredibly limited information in relation to most Taíno historical aspects and our Indigenous ancestor’s circle of life dated before colonial times. Because of that, material cultural studies of Indigenous heritage are underappreciated. In order to understand the history of Borikén (Puerto Rico), which began over 6,000 years ago, worldwide recognition is needed to diffuse the authentic revelation that the so-called New World had an organized and complex society with an enriched culture.

During the 1950s, the idea of a Caribbean sociocultural evolution intrigued some American archaeologists like Gordon Childe, Robert Redfield, Julian Stewart, and Leslie White. Their works manifested different and diverse points of view. A great number of North Americans traced sequence units of sociocultural development and they called them archaeological epochs, levels, or stages. A decade later, new studies by Herbert Spencer and Lewis Henry Morgan added advanced dimensions with regard to the understanding of the processes involved. For the past 20 years, some evolution and classification models have been deeply criticized, causing investigators to use alternative terminology. These topics related to artifacts (also called material culture) have to help to define educational and intellectual concepts in fields like visual arts, literature, architecture, urban design, and traditional popular culture.

But somehow, the pre-colonial or pre-Colombian history of Borikén and the Antilles are still a part of practical connections of production styles that are artistic guesses over artifact interpretation. These interpretations are based on research made without any type of verification concerning their social and practical uses within the archaeological findings. As a result, the historic framework used in National Parks during their conceptualization process should have adopted a greater responsible vision to inform, preserve and interpret a more complete structure of the complexity of the human experience. This would assist in the comprehension of the past in a more coherent and intelligent manner that respects our ancestorial community and their legacy. The majority of the scholastic approaches have only allowed moldable flexibility for archaeological researchers for easy identification of a specific region into supposedly appropriate descriptions based on race interaction, ethnicity, class, and genre (in and between topics) within the broader timeline of Caribbean studies.

The historic designation of Indigenous National Parks in Borikén falls into the same category with regard to their legitimacy in relation to the jurisdictional lines that this colony suffered at hands of Spain and the USA for hundreds of years. For instance, some of the cultural assessments for historic buildings and sites and their designations don't consider the strong relationship that a National Park has with state-sponsored museum projects. Even though these are two different aspects of historic conservation, parks and museums are bound together and their current status with local community involvement is crucial for their sustainability.

The area that stands out as the most important restored archaeological site in Puerto Rico is located in the Caguana neighborhood of Utuado, formerly known as Capá, a part of a region of important indigenous archaeological remains. The Caguana Ceremonial Center park consists of 10 restored bateys surrounded by a variety of stones with petroglyphs. It was rediscovered as a part of an archaeological project, with a survey done at the beginning of the XX century that was sponsored by academia and its institutional scholars from the Scientific Survey of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. This project was organized by Dr. Franz Boaz. This study was intended to create an inventory site from 1200 AD with different aspects of the recently acquired American colony. Because of that, current ongoing concerns about the possible lack of efforts for investigation, accompanied by the high precipitation conditions that affect the sites located at the mountainous inner center of the Island make preservation efforts deeply overlooked. The progressive deterioration of the remaining material culture found in these areas is an ongoing, unresolved topic. Caguana is an important region because it is considered that it has significant cultural resources that not only could provide clues about the social and political developments, but also it can be eligible for potential recognition within the framework of worldwide historic places.

On July 25th, 2005, the United Confederation of Taíno People (UCTP) and other local Indigenous groups manifested their cultural concerns with disgust regarding the deteriorating condition and management of the park to the administration of the Caguana Ceremonial Center. The Taíno people called this historic action "El Grito de Caguana" and demanded social justice for the restrictions that were imposed at the Center including their policies related to the restrained use of the site during certain hours. This resulted in a peaceful 17-day protest and hunger strike that brought international attention to the conditions that were perpetuated by maintaining colonial dependency on historic antiquity. As the issues of genocide and dominant colonialism emerged during these firm protests, the real question is why these burial grounds aren't protected from certain development damages while the real descendants of the ancestors fight for the proper preservation and protection of the site. The ideal effort for cultural recognition would be a more active public involvement that fights for constant renewal and strong revival for Indigenous parks in Borikén. But what about the restoration of museums and the historic designation that does not involve any acquisition of resources for reexamining history after colonial genocide? What kind of jobs are created in order to continue and remodel an obsolete model created by an alteration of events that needs recovery and systematic healing?

Caguana is not the largest ceremonial center, nor the only one to display petroglyphs, but it is undoubtedly unique in the Caribbean. It is located on a small terrace adjacent to the upper reaches of the Tanamá River, in the central-western mountain range, west of Utuado in Borikén. When facing to the South, it borders the igneous-plutonic massifs typical of the area, while to the North it faces unique karst formations with conical tertiary limestone dotted with small details. The 22 petroglyphs of the principal plaza has zoomorphic traits that can symbolize the ancestors of the chiefs and can be related to the sociopolitical activities done there. An in-depth study about the sociocultural aspects of the petroglyphs and artifacts that are at Caguana's museum could reestablish the lost identity of those affected by the everlasting colonialism that has perpetuated through the continuous cultural exploitation that the Caribbean still suffers.

A way to accomplish real social justice for the victims of slavery, genocide, and racial discrimination in the Caribbean is to create new discussions on Caribbean reparations that approach the problem within the Taíno context due to the ongoing violation of Indigenous rights. How the State responds to its liable responsibility of Indigenous rights matters is more about the obsolete jurisdiction laws of land management. This situation has created a dilemma regarding the genocidal stigma and abusive exploitations, which continue to be committed against Indigenous Peoples by the same States who are alleging to represent them. The concept of national patrimony has to be revisited. The only way that academia can help resolve their ongoing misappropriation within their museum curation is by acknowledging past wrongs with a deeper process that involves ‘cultural reparations’ and community involvement.