Ryan Martin presented “Ceremonial Offerings and Religious Practices Among Taíno Indians: An Archaeological Investigation of Gourd Use in Taíno Culture” at the IUSB Undergraduate Research Conference in March 1999 and at the National Conference on Undergraduate Research held in Rochester, New York in April 1999.

This research paper details gourd use in Taíno creation myths, religious ceremonies, and in everyday life by placing these practices within a broader cross-cultural framework. Martin concludes that gourds emphasized the ever present duality in Taíno culture.

Excerpt from “Ceremonial Offerings and Religious Practices Among Taíno Indians”:

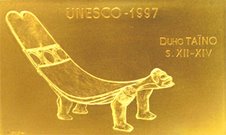

For the Taíno, religion differed from the institutionalized faiths of modern society. ‘‘The world today is accustomed to separate realms for religion and science, church and state, theology and philosophy. But for the Taínos, religion assumed all of these functions through an interlocking system of symbols, rites, and beliefs’’ (Stevens-Arroyo (1988) page 53). For the Taíno, religion incorporated all aspects of life. The central focal point of Taíno religion was the practice of cemeism. Cemies are small figurines fashioned out of stone, wood, shell and cotton. These figurines provided a physical representation of the Taíno cult of spirits. They were a link between the psychic world of humans and nature. They helped explain the chaos of life through rituals of fertility, healing and divination, and the cult of ancestors. ‘‘The cemies served as sacred mediums allowing the power of the numinous to flow in two directions; from the spirit world out into human experience, and from human need into the cosmos’’ (Stevens-Arroyo 1988). Cemies were kept by all members of the society, but those belonging to the cacique (chief) or behique (shaman or priest) were believed to hold higher powers.

Cemies could only be constructed with the assistance of a behique. For instance, if a commoner was walking in the forest and came upon a tree which he/she thought held certain powers, he/she would call a behique to come from the village and perform a prescribed ceremony. If the tree was able to answer the behique’s questions correctly and the ceremony was performed correctly, the person was able to cut the tree down and carve his/her cemi (Ramon Pane translated in Bourne 1907).

Communication with the cemies was often achieved via the use of a hallucinogenic drug, known as cohoba. This rite of using cohoba was clearly done for religious purposes. It allowed the participant to see beyond the normal.

Tree calabash or Higuero (Crescentia cujete)

To view the full paper, visit: http://www.iusb.edu/~journal/1999/Paper11.html

*UCTP Taino News Moderator’s Note: The above information is presented for educational purposes only. The views and opinions expressed within “Ceremonial Offerings and Religious Practices Among Taíno Indians: An Archaeological Investigation of Gourd Use in Taíno Culture” are not necessarily those of The Voice of the Taino People News Journal or the United Confederation of Taino People.

This research paper details gourd use in Taíno creation myths, religious ceremonies, and in everyday life by placing these practices within a broader cross-cultural framework. Martin concludes that gourds emphasized the ever present duality in Taíno culture.

Excerpt from “Ceremonial Offerings and Religious Practices Among Taíno Indians”:

For the Taíno, religion differed from the institutionalized faiths of modern society. ‘‘The world today is accustomed to separate realms for religion and science, church and state, theology and philosophy. But for the Taínos, religion assumed all of these functions through an interlocking system of symbols, rites, and beliefs’’ (Stevens-Arroyo (1988) page 53). For the Taíno, religion incorporated all aspects of life. The central focal point of Taíno religion was the practice of cemeism. Cemies are small figurines fashioned out of stone, wood, shell and cotton. These figurines provided a physical representation of the Taíno cult of spirits. They were a link between the psychic world of humans and nature. They helped explain the chaos of life through rituals of fertility, healing and divination, and the cult of ancestors. ‘‘The cemies served as sacred mediums allowing the power of the numinous to flow in two directions; from the spirit world out into human experience, and from human need into the cosmos’’ (Stevens-Arroyo 1988). Cemies were kept by all members of the society, but those belonging to the cacique (chief) or behique (shaman or priest) were believed to hold higher powers.

Cemies could only be constructed with the assistance of a behique. For instance, if a commoner was walking in the forest and came upon a tree which he/she thought held certain powers, he/she would call a behique to come from the village and perform a prescribed ceremony. If the tree was able to answer the behique’s questions correctly and the ceremony was performed correctly, the person was able to cut the tree down and carve his/her cemi (Ramon Pane translated in Bourne 1907).

Communication with the cemies was often achieved via the use of a hallucinogenic drug, known as cohoba. This rite of using cohoba was clearly done for religious purposes. It allowed the participant to see beyond the normal.

Tree calabash or Higuero (Crescentia cujete)

To view the full paper, visit: http://www.iusb.edu/~journal/1999/Paper11.html

*UCTP Taino News Moderator’s Note: The above information is presented for educational purposes only. The views and opinions expressed within “Ceremonial Offerings and Religious Practices Among Taíno Indians: An Archaeological Investigation of Gourd Use in Taíno Culture” are not necessarily those of The Voice of the Taino People News Journal or the United Confederation of Taino People.

No comments:

Post a Comment