Showing posts with label Jose Barreiro. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Jose Barreiro. Show all posts

12/16/2013

12/04/2012

Based on a True Story, Taino Novel Republished

New York (UCTP Taino News) – Dr. Jose Barreiro's masterfully written historical novel chronicling the first encounters between Indigenous Peoples and Europeans beginning with Columbus has been re-released by Fulcrum Press under the title “Taino: A Novel.” The story is told from the point of view of Guaikan/Diego, Christopher Columbus' young adopted Taino Indian son and interpreter. The book vividly recreates the often violent clashes of cultures in the Caribbean during the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

Author Jose Barreiro notes “My first publisher opted for a more generic title, and thus ‘The Indian Chronicles.’” He continued stating ““I always thought the book was best titled ‘Taino,’ as it tells the story of a Taino memory.”

Indeed, the engaging and at times heartbreaking story is told four decades after the arrival of Columbus, when Guaikan is an elderly man. While the story is historical fiction, it is based on true historical events and figures.

Presently a senior fellow at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, Jose Barreiro is a novelist, essayist, and an activist of nearly four decades on American indigenous hemispheric themes. “Taino: A Novel” is currently available at Amazon.com.

UCTPTN 12.04.2012

7/13/2012

Taíno Flag Presented to National Museum of the American Indian

|

| José Barreiro accepts Taino Confederation flag on behalf of the Smithsonian Institution |

Washington

D.C. (UCTP Taino News) - On Friday, July 13 2012, the flag of the United

Confederation of Taíno People was formally presented to the Smithsonian’s

National Museum of the American Indian. The flag will now become part of the

Museum’s permanent collection and is scheduled to be displayed annually along

with the flags of other Indigenous Peoples of the Western Hemisphere during the observance of Native

American Heritage month. The Taíno flag was presented to José Barreiro, the Museum’s Assistant Director for Research by Confederation

President Roberto Mukaro Borrero. The historic flag presentation opened a public

symposium entitled “Beyond Extinction: Updates from the Field”, a program that

culminated a week long workshop session focusing on indigenous Taíno related

themes.

UCTPTN

07.08.2012

1/03/2007

Living in America: The Allure of Gold

presents

Living in America: The Allure of Gold

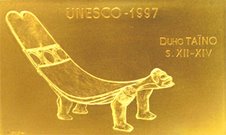

Gold is an enduring icon of wealth, beauty and power. Immortalized in the daily lives and cultural beliefs of ancient peoples, it was the first metal worked by humans; today it is still the most universal currency. Deposits of gold have been found on every continent except Antarctica. Gold also played a compelling role in the history of the Americas. Beginning with the voyages of Columbus through the Gold Rush era that drove a massive migration westward; this precious metal is a part of the formation of the American identity. This year’s Living in America theme recognizes the expressions, effects and allure that gold has on culture through exciting musical performances, discussions, and films for adults and families.

Ancient Expression…

Sunday, January 14

Kaufmann Theater and Linder Theaters, First Floor

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

These programs focus on pre-Columbian cultures that have used and cherished gold…

Atl-Tlachinolli

Mexican Indigenous Dance • 1:00pm • Kaufmann Theater

Mexica dance group Atl-Tlachinolli performs the centuries-old indigenous ritual dance traditions of the Aztecs. The vibrant and colorful music and dance presentation begins with ceremonial recognition of the four directions and dances conducted in four cycles. The group makes use of pre-Columbian instruments, rhythms, and regalia.

El Dorado Revisited

Panel Discussion • 2:00 p.m. • Linder Theater

Representatives of several indigenous communities present their perspectives on pre-Columbian relationships to gold and the effects that 15th century colonization fueled by the search for gold had upon these communities. Invited panelist include Jose Barreiro Ph.D. (Guajiro Taino, Cuba), Assistant Director of Research, National Museum of the American Indian; Mirian Mazaquiza (Quechua, Ecuador), Program Officer, United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues Secretariat; and George Simon (Lokono Arawak, Guyana), critically acclaimed artist. A question and answer session will follow.

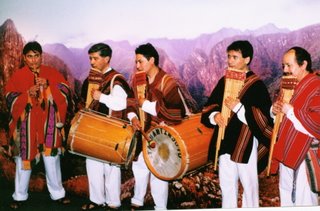

Tahauntinsuyo*

Andean Music Concert • 4:00 p.m. • Kaufmann Theater

Tahuantinsuyo, a group of traditional Andean musicians, will perform music from the ancient Incan empire, now the countries of Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Argentina, Bolivia and Colombia. Performing together internationally for over 20 years, the group uses an array of pan-pipes, flutes, drums, string instruments, and colorful traditional clothing. A series of stunning slides featuring the geography and culture of the Andes will enhance the program.

Special Event

AMNH Indigenous Crafts Fair and Artist Showcase

Grand Gallery • 11:00 a.m. -5:00 p.m.

In conjunction with AMNH’s exhibition “Gold”, experience a crafts fair and artist showcase highlighting various indigenous communities linked with pre-Columbian gold traditions in the Grand Gallery at the 77th Street entrance. Some of the acclaimed artists showcasing works include Inty Muenala (Quechua, Ecuador), Mildred Torres Speeg (Boriken Taino, Puerto Rico), George Simon (Lokono Arawak, Guyana), and others.

Taino Warrior by Mildred Torres-Speeg

All programs are free with suggested Museum admission. Neither tickets nor reservations are required. Seating is limited and is on a first-come, first-served basis. It is recommended that you arrive in plenty of time to enter the Museum and locate the program space. Please use the main entrance at Central Park West at 79th Street.

For further information, call the Museum's Department of Education at 212-769-5315 between 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. weekdays. Program information is also available on the Museum’s Web site at www.amnh.org/livinginamerica/ A three-story parking garage is open during Museum hours; enter from West 81st Street. For public transportation, call 212-769-5100.

Living in America/Global Weekends are made possible, in part, by The Coca-Cola Company, the City of New York, and the New York City Council. Additional support has been provided by the May and Samuel Rudin Family Foundation, Inc., the Tolan Family, and the family of Frederick H. Leonhardt.

*This artist appears as part of the American Museum of Natural History’s World Music Live series supported by The New York State Music Fund, established by the New York State Attorney General at

Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors.

Program Curators: Roberto Múcaro Borrero (Boriken Taíno), Teddy Yoshikami

9/23/2004

Born Puerto Rican, born (again) Taino? A resurgence of indigenous identity among Puerto Ricans has sparked debates...

Born Puerto Rican, born (again) Taino? A resurgence of indigenous identity among Puerto Ricans has sparked debates over the island's tri-racial history.

by Cristina Veran

In 2000, a popular hip-hop DJ from New York Tony Touch released The Piece Maker, a mix CD that presented his signature melding of rap lyrics and break-beats, spiked with a smattering of Latino-Caribbean sounds that effectively bind together the artist's Puerto Rican and hip-hop origins. Beyond the tracks and the rap however, this CD's cover art drew attention to a whole other kind of mixing: two otherwise mirror-image photos of himself--one in more typical streetwear-donning repose, the other sprouting a shock of azure feathered headdress, face painted in a geometric maze of dotted patterns and red and black swashes.

Not your typical rap regalia, to be sure, but this stylistic manifestation epresented an even more personal group-identity for the artist also known as the Taino Turntable Terrorist in homage to his indigenous (Taino Indian) ancestry. The CD's opening track, "Toca's Intro" boasted with a playful defiance: I shine all over the world wit my sonido/ Mijo, you ain't got nothing on this Taino/ I'm half Indian, but my name ain't Tonto.

Today, spurred as much perhaps by pop culture references like Touch's album as the general post-civil rights era search for identity among communities of color, young and old Puerto Ricans have increasingly looked toward the Indian component of their presumed tri-racial history for alternative interpretations of what makes them, in essence, who they are. Already--and increasingly so within the past 15 years--it is common, among both the Taino-representing and not, to self-identify using the term "Boricua"; a Taino term denoting a native to the island originally called "Boriken" (sometimes spelled Borinquen) and renamed Puerto Rico ("rich port") by Spain.

Conquest and "Extinction"

Tainos were the first "Americans" to greet Christopher Columbus and Co.'s earliest voyages, first to be mistaken for and hence misnamed "Indian." Spanish chroniclers like Bartolome de Las Casas estimated their population to be upwards of a million--as much as 8 million, when including neighboring island indigenes in the count--and yet within a 100 years of civilization-clashing, this estimate dropped dramatically until they ceased to be counted as a distinct group in the colonial census, relegated ever after to an undocumented oblivion.

The most widely held, schoolbook-promoted belief about Boriken's Tainos goes something like this: they were quickly wiped out, wholesale, by Spanish attrocities and Old World diseases, existing only in the collective memory of a glorious pre-Colombian past. The Encyclopedia Britannica apparently concurs, defining the Taino as an "extinct Arawak Indian group," whose "extinction" was complete "within 100 years of Spanish conquest."

The alternative, more accommodating explanation, first espoused during the 1940s and '50s as Puerto Rico shifted to Commonwealth from Unincorporated Territory status, promotes a mixed-race ideal akin to the raza cosmica (mixed "cosmic race") ideal conceptualized by Mexico's Jose Vasconcelos. For these philosophical adherents, the Taino continue to exist only as subsumed elements within Puerto Rico's tri-racial dynamic.

Finally the third view, oft-contested in Puerto Rican academic circles, maintains that not only is the Amerindian component far from extinct among present-day Puerto Ricans (for many of whom a distinctly indigenous Taino identity has endured), but that it can and does thrive.

At the forefront of this movement have been the still-growing number of so-called "revivalist" groups, from the Taino Inter-Tribal Council to Nacion Taino to the Jaribonicu Taino Tribal Nation, whose emergence as organized bodies began to coalesce.

"This first arose as an elitist movement," explains Gabriel Haslip-Viera, a professor at New York's City College and former director of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. "[Identifying as] Taino was a way of separating themselves from the Europeans, and so Puerto Ricans began claiming at least some sort of Taino background whether they had any or not." In the Taino, ultimately, they believed they had found an uncontestable validation for their anti-colonialist struggle.

The quintessential Puerto Rican, enshrined in the island's official seal and by the early nationalists, embodies an inseparably-hinged triptych comprised of red (American Indian), white (Iberian), and black (West African) components. As Cuba's Jose Marti proclaimed of Latin Americans: "One may descend from the fathers of Valencia and mothers of the Canary Islands, yet regard as one's own the blood of the heroic, naked Caracas warriors which stained the craggy ground where they met the armored Spanish soldier."

Conflicting Identities

Among the loudest detractors of an indigenous-centered Puerto Rican identity, meanwhile, have been those for whom a more African-centered reality speaks to their experience. Taino resurgence, for them, is seen (by some) as having been exploited as a too-convenient, less racially-problematic alternative to the island's African-derived culture and gene pool Indigenous revivalism is seen as pitting a more mythologized Indian identity against a black reality.

The growing number of island-based and internationally active Taino organizations, who insist the modern-day Taino identity is much more than myth, believe their cause has been strengthened by a groundbreaking genetic study spearheaded by Juan Carlos Martinez Cruzado a molecular biologist based at the University of Puerto Rico's Mayaguez campus.

The Taino genome project genome project 1 The Human Genome Project, see there 2. A general term for a coordinated research initiative for mapping and sequencing the genome of any organism , which was initiated in 1999 through a grant from the National Science Foundation to test mitochondrial mitochondrial throughout the island, has identified a heretofore improbable-sounding 62 percent majority of Puerto Ricans today as of Amerindian Taino, descent.

How valid, then, are the assertions, not to mention the history books, which discount Puerto Rican claims to an identity for which so many may turn out to have direct genealogical ties?

Haslip-Viera, who edited the groundbreaking text Taino Revival, is among the prominent scholars who remain skeptical. "It might indeed be the case that somewhere in the family tree, going all the way back to the 16th century, there might have been one indigenous woman whose DNA has been carried through all the generations until the current bloodline "And yet during all the years since that, there have been all these other peoples who have come in from Africa, from Europe, from Asia [referring to the South Asian and Chinese laborers who also came to the islands, not typically included in the Hispanic Caribbean discourse on race]."

"Why focus on this one element which is so minor compared with other elements?" he questions.

"Over the long term," contends Haslip-Viera, "that indigenous element in the genome is really quite meaningless."

For those like Roberto Mucaro Borrero, however, there is profound meaning. Borrero, a leader of the United Confederacy of Taino People, argues that, rather than deriving from an exclusionary, nationalistic posture, Taino self/community identification is about affirming the very indigeneity of most Puerto Ricans, irrespective of blood quantum--and guaranteeing the sovereign rights inherent in such claims. Borrero sees the insistent discounting of Taino revivalism predominant in academia as racism, plain and simple; the emphasis on a nonspecific mixed-raced Puerto Rican identity as misplaced, at best. “This westernized, homogenized Latino thing is an inequitable concept where indigenous peoples are concerned," he believes.

"I have a real problem," Borrero adds, "when those people preferring to affirm an African or even a Spanish side to their history say that I can't affirm who I am as an indigenous person, as though everybody else is entitled to be who they are on our ancestral homeland, except us."

Drops of Blood

The populations of Mexico, Guatemala, Ecuador, and other South and Central American countries are overwhelmingly of Amerindian descent when statistics include those of mixed Spanish-Indian, Afro-Indian, or tri-racial lineage. The dominant mainstream culture in each, however, imposes and reinforces a decidedly Eurocentric ideal, far more Spanish than indigenous (or African, for that matter) in language, standards of beauty, and cultural mores.

In the United States, meanwhile, where individuals of native ancestry (including those of mixed race) comprise a mere single-digit percentage, more than 500 tribal nations celebrate their distinct indigenous heritage. Puerto Rico, while clearly understood to be part of Latin America, is heavily influenced by the United States in some of its collective attitudes toward race and indigeneity.

"In U.S. society, among the Anglo establishment, Indians are romanticized to a large extent," explains Haslip-Viera. "It's not this way in, say, Bolivia or Peru."

In the U.S., "one drop" became enough to certify blackness, initially in an attempt to maintain the pool of slave labor indefinitely. For Native Americans, a federally imposed concept of blood quantum was instead designed to deconstruct identity as the gene pools presumably would become mixed, gradually legislating away indigenous claims to land and sovereign rights. The sooner someone could no longer legally be recognized as Indian, the sooner white settlers and government agencies could move in for the (literal or figurative) kill.

The U.S. government, meanwhile, imposed the strictest race-defining standard yet for non-white citizens upon Native Hawai'ians. In direct opposition to Hawai'ian custom, in which identity (hence, indigeneity) comes from one's genealogical links to ancestors, Hawai'ians must prove a minimum 50 percent blood quantum for certain governmental benefits. At the same time, self-identifying and community-acknowledged Hawai'ians leading the fight for self-determination may themselves also have Scottish, Filipino, Japanese, even mixed Puerto Rican forebears in their family trees. For them, without question, the tree itself remains essentially Hawai'ian.

While by no means suggesting that either he or the bulk of today's Tainos are of racially-pure Amerindian stock, Borrero contends that the multi-hued genetic mix of the island and its diaspora does not erase the indigeneity of Taino-descended Puerto Ricans. Rather than Taino being merely absorbed within other groups, he believes, "All of those people who came to Boriken after Columbus ... they became part of our genealogy, our Taino narrative."

The Puerto Rican narrative, in a literary sense, does have a real history of romanticizing the Taino to suit the aforementioned nationalist ideal—that Puerto Ricans' sovereign right to a fully autonomous homeland are strengthened by an inherent indigenous connection to the land.

In his essay "Making Indians Out of Blacks," scholar Jorge Duany of Puerto Rico's University of the Sacred Heart notes that prominent writers and intellectuals from Eugenio Maria de Hostos to Juan Antonio Corretjer "have employed the Taino figure as an inspiration in the unfinished quest for the island's freedom." At the same time, Duany reinforces the prevailing assertions in academia when he argues, "The indigenista discourse has contributed to the erasure of the ethnic and cultural practices of blacks in Puerto Rico."

David Velasquez Muhammad is one young Puerto Rican for whom a black identity is paramount to his understanding of self. His "beef," says the Madison, Wisconsin-based youth organizer for the Nation of Islam's growing Latino Ministry, lies not with Taino groups themselves or their assertions to legitimacy. Rather, Muhammad sharply derides "the Puerto Rican Institute of Culture and other bourgeois institutions, for their promotion of a conceivably less-threatening, mystified promoting Taino culture not through living, breathing, modern people but exclusively through objects and artifacts--including human remains--on display behind glass-cased exhibitions.

Perhaps those who publicly refute the validity of a contemporary Taino identity could better direct their arguments toward these institutions themselves, rather than the so-called Taino revivalists.

Cultural Survival

While the DNA research suggests, encouragingly, the persistance of Taino genealogy into the present, what of the less-quantifiable, more-abstract components commonly understood to characterize and denote a distinct people?

Unquestionably the Taino have suffered periods of disconnection and loss from much of their culture, their language, and spirituality under both sword and Church. This initial victimization under colonialism need not necessarily be understood as a perpetual state of loss for the Taino.

New Zealand's indigenous Maori, for example--often as genetically diverse as the Taino-identifying Puerto Ricans--have achieved great success in the reclamation and renewed promulgation of the same Maori language once presumed near death by the mid-20th century. From the establishment of "kohanga reo" Maori language immersion schools, to dual-language hip-hop video shows on broadcast TV, to an all-Maori radio network, New Zealand's example proves that it can be done. Maori achievements in language revival have subsequently inspired similarly intensive undertakings by Native Hawai'ians in Hawai'i and the Blackfoot Nation in the continental U.S.

Modern-day Tainos seeking the same kind of rebirth do so at an apt time. The recent formation of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, a body representing indigenous peoples on all continents, has focused on exactly these concerns. High-level contributions of Tainos to this and other indigenous forums, including Roberto Mucaro Borrero's co-chairing of the NGO Committee for the International Decade of the World's Indigenous Peoples and Cuban Taino Jose Barreiro's editorship of Cornell University's prestigious Native Americas journal--has increased the public profile of Taino discourse in activist, academic, and social circles.

In the years to come, Puerto Ricans of varying extractions will surely continue to contemplate, perhaps even re-evaluate, what being Boricua means for them. Today's Taino are enabled as never before to ensure they remain essential to this process.

Cristina Veran is a journalist, historian, and educator who is also a United Nations correspondent. Her work has appeared in Ms. Magazine, Vibe, Oneworld, and News From Indian Country.

This article originally appears in COLORLINES Magazine Copyright 2003

by Cristina Veran

In 2000, a popular hip-hop DJ from New York Tony Touch released The Piece Maker, a mix CD that presented his signature melding of rap lyrics and break-beats, spiked with a smattering of Latino-Caribbean sounds that effectively bind together the artist's Puerto Rican and hip-hop origins. Beyond the tracks and the rap however, this CD's cover art drew attention to a whole other kind of mixing: two otherwise mirror-image photos of himself--one in more typical streetwear-donning repose, the other sprouting a shock of azure feathered headdress, face painted in a geometric maze of dotted patterns and red and black swashes.

Not your typical rap regalia, to be sure, but this stylistic manifestation epresented an even more personal group-identity for the artist also known as the Taino Turntable Terrorist in homage to his indigenous (Taino Indian) ancestry. The CD's opening track, "Toca's Intro" boasted with a playful defiance: I shine all over the world wit my sonido/ Mijo, you ain't got nothing on this Taino/ I'm half Indian, but my name ain't Tonto.

Today, spurred as much perhaps by pop culture references like Touch's album as the general post-civil rights era search for identity among communities of color, young and old Puerto Ricans have increasingly looked toward the Indian component of their presumed tri-racial history for alternative interpretations of what makes them, in essence, who they are. Already--and increasingly so within the past 15 years--it is common, among both the Taino-representing and not, to self-identify using the term "Boricua"; a Taino term denoting a native to the island originally called "Boriken" (sometimes spelled Borinquen) and renamed Puerto Rico ("rich port") by Spain.

Conquest and "Extinction"

Tainos were the first "Americans" to greet Christopher Columbus and Co.'s earliest voyages, first to be mistaken for and hence misnamed "Indian." Spanish chroniclers like Bartolome de Las Casas estimated their population to be upwards of a million--as much as 8 million, when including neighboring island indigenes in the count--and yet within a 100 years of civilization-clashing, this estimate dropped dramatically until they ceased to be counted as a distinct group in the colonial census, relegated ever after to an undocumented oblivion.

The most widely held, schoolbook-promoted belief about Boriken's Tainos goes something like this: they were quickly wiped out, wholesale, by Spanish attrocities and Old World diseases, existing only in the collective memory of a glorious pre-Colombian past. The Encyclopedia Britannica apparently concurs, defining the Taino as an "extinct Arawak Indian group," whose "extinction" was complete "within 100 years of Spanish conquest."

The alternative, more accommodating explanation, first espoused during the 1940s and '50s as Puerto Rico shifted to Commonwealth from Unincorporated Territory status, promotes a mixed-race ideal akin to the raza cosmica (mixed "cosmic race") ideal conceptualized by Mexico's Jose Vasconcelos. For these philosophical adherents, the Taino continue to exist only as subsumed elements within Puerto Rico's tri-racial dynamic.

Finally the third view, oft-contested in Puerto Rican academic circles, maintains that not only is the Amerindian component far from extinct among present-day Puerto Ricans (for many of whom a distinctly indigenous Taino identity has endured), but that it can and does thrive.

At the forefront of this movement have been the still-growing number of so-called "revivalist" groups, from the Taino Inter-Tribal Council to Nacion Taino to the Jaribonicu Taino Tribal Nation, whose emergence as organized bodies began to coalesce.

"This first arose as an elitist movement," explains Gabriel Haslip-Viera, a professor at New York's City College and former director of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. "[Identifying as] Taino was a way of separating themselves from the Europeans, and so Puerto Ricans began claiming at least some sort of Taino background whether they had any or not." In the Taino, ultimately, they believed they had found an uncontestable validation for their anti-colonialist struggle.

The quintessential Puerto Rican, enshrined in the island's official seal and by the early nationalists, embodies an inseparably-hinged triptych comprised of red (American Indian), white (Iberian), and black (West African) components. As Cuba's Jose Marti proclaimed of Latin Americans: "One may descend from the fathers of Valencia and mothers of the Canary Islands, yet regard as one's own the blood of the heroic, naked Caracas warriors which stained the craggy ground where they met the armored Spanish soldier."

Conflicting Identities

Among the loudest detractors of an indigenous-centered Puerto Rican identity, meanwhile, have been those for whom a more African-centered reality speaks to their experience. Taino resurgence, for them, is seen (by some) as having been exploited as a too-convenient, less racially-problematic alternative to the island's African-derived culture and gene pool Indigenous revivalism is seen as pitting a more mythologized Indian identity against a black reality.

The growing number of island-based and internationally active Taino organizations, who insist the modern-day Taino identity is much more than myth, believe their cause has been strengthened by a groundbreaking genetic study spearheaded by Juan Carlos Martinez Cruzado a molecular biologist based at the University of Puerto Rico's Mayaguez campus.

The Taino genome project genome project 1 The Human Genome Project, see there 2. A general term for a coordinated research initiative for mapping and sequencing the genome of any organism , which was initiated in 1999 through a grant from the National Science Foundation to test mitochondrial mitochondrial throughout the island, has identified a heretofore improbable-sounding 62 percent majority of Puerto Ricans today as of Amerindian Taino, descent.

How valid, then, are the assertions, not to mention the history books, which discount Puerto Rican claims to an identity for which so many may turn out to have direct genealogical ties?

Haslip-Viera, who edited the groundbreaking text Taino Revival, is among the prominent scholars who remain skeptical. "It might indeed be the case that somewhere in the family tree, going all the way back to the 16th century, there might have been one indigenous woman whose DNA has been carried through all the generations until the current bloodline "And yet during all the years since that, there have been all these other peoples who have come in from Africa, from Europe, from Asia [referring to the South Asian and Chinese laborers who also came to the islands, not typically included in the Hispanic Caribbean discourse on race]."

"Why focus on this one element which is so minor compared with other elements?" he questions.

"Over the long term," contends Haslip-Viera, "that indigenous element in the genome is really quite meaningless."

For those like Roberto Mucaro Borrero, however, there is profound meaning. Borrero, a leader of the United Confederacy of Taino People, argues that, rather than deriving from an exclusionary, nationalistic posture, Taino self/community identification is about affirming the very indigeneity of most Puerto Ricans, irrespective of blood quantum--and guaranteeing the sovereign rights inherent in such claims. Borrero sees the insistent discounting of Taino revivalism predominant in academia as racism, plain and simple; the emphasis on a nonspecific mixed-raced Puerto Rican identity as misplaced, at best. “This westernized, homogenized Latino thing is an inequitable concept where indigenous peoples are concerned," he believes.

"I have a real problem," Borrero adds, "when those people preferring to affirm an African or even a Spanish side to their history say that I can't affirm who I am as an indigenous person, as though everybody else is entitled to be who they are on our ancestral homeland, except us."

Drops of Blood

The populations of Mexico, Guatemala, Ecuador, and other South and Central American countries are overwhelmingly of Amerindian descent when statistics include those of mixed Spanish-Indian, Afro-Indian, or tri-racial lineage. The dominant mainstream culture in each, however, imposes and reinforces a decidedly Eurocentric ideal, far more Spanish than indigenous (or African, for that matter) in language, standards of beauty, and cultural mores.

In the United States, meanwhile, where individuals of native ancestry (including those of mixed race) comprise a mere single-digit percentage, more than 500 tribal nations celebrate their distinct indigenous heritage. Puerto Rico, while clearly understood to be part of Latin America, is heavily influenced by the United States in some of its collective attitudes toward race and indigeneity.

"In U.S. society, among the Anglo establishment, Indians are romanticized to a large extent," explains Haslip-Viera. "It's not this way in, say, Bolivia or Peru."

In the U.S., "one drop" became enough to certify blackness, initially in an attempt to maintain the pool of slave labor indefinitely. For Native Americans, a federally imposed concept of blood quantum was instead designed to deconstruct identity as the gene pools presumably would become mixed, gradually legislating away indigenous claims to land and sovereign rights. The sooner someone could no longer legally be recognized as Indian, the sooner white settlers and government agencies could move in for the (literal or figurative) kill.

The U.S. government, meanwhile, imposed the strictest race-defining standard yet for non-white citizens upon Native Hawai'ians. In direct opposition to Hawai'ian custom, in which identity (hence, indigeneity) comes from one's genealogical links to ancestors, Hawai'ians must prove a minimum 50 percent blood quantum for certain governmental benefits. At the same time, self-identifying and community-acknowledged Hawai'ians leading the fight for self-determination may themselves also have Scottish, Filipino, Japanese, even mixed Puerto Rican forebears in their family trees. For them, without question, the tree itself remains essentially Hawai'ian.

While by no means suggesting that either he or the bulk of today's Tainos are of racially-pure Amerindian stock, Borrero contends that the multi-hued genetic mix of the island and its diaspora does not erase the indigeneity of Taino-descended Puerto Ricans. Rather than Taino being merely absorbed within other groups, he believes, "All of those people who came to Boriken after Columbus ... they became part of our genealogy, our Taino narrative."

The Puerto Rican narrative, in a literary sense, does have a real history of romanticizing the Taino to suit the aforementioned nationalist ideal—that Puerto Ricans' sovereign right to a fully autonomous homeland are strengthened by an inherent indigenous connection to the land.

In his essay "Making Indians Out of Blacks," scholar Jorge Duany of Puerto Rico's University of the Sacred Heart notes that prominent writers and intellectuals from Eugenio Maria de Hostos to Juan Antonio Corretjer "have employed the Taino figure as an inspiration in the unfinished quest for the island's freedom." At the same time, Duany reinforces the prevailing assertions in academia when he argues, "The indigenista discourse has contributed to the erasure of the ethnic and cultural practices of blacks in Puerto Rico."

David Velasquez Muhammad is one young Puerto Rican for whom a black identity is paramount to his understanding of self. His "beef," says the Madison, Wisconsin-based youth organizer for the Nation of Islam's growing Latino Ministry, lies not with Taino groups themselves or their assertions to legitimacy. Rather, Muhammad sharply derides "the Puerto Rican Institute of Culture and other bourgeois institutions, for their promotion of a conceivably less-threatening, mystified promoting Taino culture not through living, breathing, modern people but exclusively through objects and artifacts--including human remains--on display behind glass-cased exhibitions.

Perhaps those who publicly refute the validity of a contemporary Taino identity could better direct their arguments toward these institutions themselves, rather than the so-called Taino revivalists.

Cultural Survival

While the DNA research suggests, encouragingly, the persistance of Taino genealogy into the present, what of the less-quantifiable, more-abstract components commonly understood to characterize and denote a distinct people?

Unquestionably the Taino have suffered periods of disconnection and loss from much of their culture, their language, and spirituality under both sword and Church. This initial victimization under colonialism need not necessarily be understood as a perpetual state of loss for the Taino.

New Zealand's indigenous Maori, for example--often as genetically diverse as the Taino-identifying Puerto Ricans--have achieved great success in the reclamation and renewed promulgation of the same Maori language once presumed near death by the mid-20th century. From the establishment of "kohanga reo" Maori language immersion schools, to dual-language hip-hop video shows on broadcast TV, to an all-Maori radio network, New Zealand's example proves that it can be done. Maori achievements in language revival have subsequently inspired similarly intensive undertakings by Native Hawai'ians in Hawai'i and the Blackfoot Nation in the continental U.S.

Modern-day Tainos seeking the same kind of rebirth do so at an apt time. The recent formation of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, a body representing indigenous peoples on all continents, has focused on exactly these concerns. High-level contributions of Tainos to this and other indigenous forums, including Roberto Mucaro Borrero's co-chairing of the NGO Committee for the International Decade of the World's Indigenous Peoples and Cuban Taino Jose Barreiro's editorship of Cornell University's prestigious Native Americas journal--has increased the public profile of Taino discourse in activist, academic, and social circles.

In the years to come, Puerto Ricans of varying extractions will surely continue to contemplate, perhaps even re-evaluate, what being Boricua means for them. Today's Taino are enabled as never before to ensure they remain essential to this process.

Cristina Veran is a journalist, historian, and educator who is also a United Nations correspondent. Her work has appeared in Ms. Magazine, Vibe, Oneworld, and News From Indian Country.

This article originally appears in COLORLINES Magazine Copyright 2003

8/17/2004

Historians work to set record straight on Cuba's Taino Indians

BY GARY MARX

Chicago Tribune

YARA, Cuba - (KRT) - In a sweltering coastal settlement, Alejandro Hartmann pulled out a spiral notebook and jotted notes as a local peasant described his family's ties to a long forgotten indigenous group that is witnessing a modest resurgence.

"What is the name of your mother and father?" Hartmann asked Julio Fuentes, a wisp of a man parked on a wooden bench. "Where do they live? How old are they?"

Hartmann fired off a dozen more questions as part of his effort to complete the first census of the descendants of the Taino Indians, an indigenous group that once thrived in this remote region of eastern Cuba and later were thought to be extinct.

"Julio is a mixture of Spanish and Indian like many people," explained Hartmann, a historian and Taino expert. "I want to eliminate the myth once and for all that the Indians were extinguished in Cuba."

For years, anthropologists widely believed this island's once-powerful Taino Indians were exterminated shortly after Christopher Columbus sailed into a pristine bay and walked the steep, thickly forested terrain more than 500 years ago.

The explorer spent only a week in the area in 1492 but described the Taino as gentle, hard-working people growing crops and navigating the crystalline waters in huge dug-out canoes.

But, in a familiar story throughout the Americas, war and disease decimated the Taino, whose sense of identity was further razed over the centuries by racism and by generations of intermixing with whites, blacks and others who settled here.

Today, it's difficult to differentiate Taino descendents from the average Cuban peasant, or guajiro, as they are called.

Yet, Hartmann and a group of experts continue to press ahead, rewriting the tale of the Taino's demise in an effort to set the historical record straight and foster recognition among the island's 11 million residents of the group's contribution to Cuban life.

With a new museum, academic conferences and other projects, they also are trying to nurture a nascent sense of identity among the hundreds - perhaps thousands - of Taino descendents who are scattered along Cuba's impoverished eastern tip.

"We are recovering knowledge that was forgotten, knowledge that my parents and grandparents had," said Fuentes, 51. "A lot of people had knowledge but lived and died without knowing its Indian origin."

Experts say Taino influences are everywhere.

The palm-thatched huts common in the region are similar to those built centuries ago by the indigenous group. Some farmers till the soil using a long, sharpened pole known to the Taino as a coa.

Fuentes said he uses a coa to remove old plantain trees and dig latrines, while harvesting beans, sweet potatoes and other crops according to the four lunar phases - a belief system of indigenous origin.

Some coastal residents fish with small nets in the Taino style and crabs are trapped using a crude, box-shaped device that has changed little over the centuries, experts say.

Although the Taino language, Arawak, has all but died in Cuba, hundreds of indigenous words are peppered throughout the local Spanish. Many of the names of the island's most well-known places - from Havana to Camaguey to Baracoa - come from the Arawak language.

"The Taino culture permeates the culture of Cuba in a fundamental way," explained Jose Barreiro, a Cuban-American scholar of Taino history. "It's the base culture of the country along with Spanish and African influences."

Experts say the Taino migrated north from South America's Amazon basin centuries ago, populating much of what is now Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and Cuba.

The Taino arrived in Cuba about 300 years before Columbus and eventually numbered in the hundreds of thousands.

Organized in villages under the authority of caciques or chiefs, the Taino cultivated beans, yucca, corn and other crops, along with something they called cohiba, or tobacco.

They hunted turtles, snakes, iguanas and a giant rodent called a jutia, while also adhering to a complex set of spiritual beliefs whose primary deity, Yucahuguama, represented agriculture and the ocean.

Roberto Ordunez, an anthropologist and director of the Taino museum in Baracoa, a picturesque colonial town of 50,000, said Columbus described a large, thriving agricultural community.

"I climbed up a mountain and found the flat lands planted with many things," Ordunez said Columbus observed in his journal in 1492. "It was a pleasure to see it and in the middle of it was a large population."

Although the Taino left no large monuments, they built canals for channeling water, caves for storing food during drought and a network of stone footpaths for travel and to escape their enemies, a raiding tribe known as the Carib.

But the Taino had no chance against the Spanish, who brought malaria, smallpox and other deadly diseases, along with modern weapons.

Still, some put up a fight.

An indigenous leader named Hatuey traveled from the island of Hispaniola to Baracoa to warn the Tainos about the conquistadores. He was captured, refused to convert to Christianity and was burned at the stake.

Hatuey remains a revered figure in Cuba, where his story is among the first lessons taught to schoolchildren.

"Hatuey is considered the first rebel in America because he was the first to understand the abuses of the colonialists and rebel against them," explained Noel Cautin, a guide at the Taino museum.

A second indigenous leader, Guama, launched hit-and-run attacks against the conquistadores for a decade before he was killed, perhaps by his own brother, in 1532. By then, the Taino numbered only a few thousand, a figure that continued to plummet. Historians in the 19th century declared there were no indigenous left on the island.

"Those who remained were in remote areas and the historians were primarily in the cities," Barriero said. "The Taino also had adopted Spanish technology and language."

Barriero and others say that not a single Taino community remains intact, though the group's culture is best preserved in La Caridad de los Indios and a handful of other remote villages in the mountains southwest of Baracoa.

In a sign of growing international recognition, the Smithsonian Institution last year returned bone fragments from seven Taino Indians to the La Caridad community for a sacred reburial.

The human remains along with thousands of indigenous artifacts were taken almost a century ago by American archaeologist Mark Harrington and later fell into the possession of the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian.

Another source of pride is Baracoa's modest Taino museum, which opened last year in a hillside cave and displays pendants, necklaces and other pre-Columbian artifacts made of shells and other materials.

Fuentes has visited the museum twice.

"I felt pride because I hadn't see these things before and because I'm part of this culture," he said.

Chicago Tribune

YARA, Cuba - (KRT) - In a sweltering coastal settlement, Alejandro Hartmann pulled out a spiral notebook and jotted notes as a local peasant described his family's ties to a long forgotten indigenous group that is witnessing a modest resurgence.

"What is the name of your mother and father?" Hartmann asked Julio Fuentes, a wisp of a man parked on a wooden bench. "Where do they live? How old are they?"

Hartmann fired off a dozen more questions as part of his effort to complete the first census of the descendants of the Taino Indians, an indigenous group that once thrived in this remote region of eastern Cuba and later were thought to be extinct.

"Julio is a mixture of Spanish and Indian like many people," explained Hartmann, a historian and Taino expert. "I want to eliminate the myth once and for all that the Indians were extinguished in Cuba."

For years, anthropologists widely believed this island's once-powerful Taino Indians were exterminated shortly after Christopher Columbus sailed into a pristine bay and walked the steep, thickly forested terrain more than 500 years ago.

The explorer spent only a week in the area in 1492 but described the Taino as gentle, hard-working people growing crops and navigating the crystalline waters in huge dug-out canoes.

But, in a familiar story throughout the Americas, war and disease decimated the Taino, whose sense of identity was further razed over the centuries by racism and by generations of intermixing with whites, blacks and others who settled here.

Today, it's difficult to differentiate Taino descendents from the average Cuban peasant, or guajiro, as they are called.

Yet, Hartmann and a group of experts continue to press ahead, rewriting the tale of the Taino's demise in an effort to set the historical record straight and foster recognition among the island's 11 million residents of the group's contribution to Cuban life.

With a new museum, academic conferences and other projects, they also are trying to nurture a nascent sense of identity among the hundreds - perhaps thousands - of Taino descendents who are scattered along Cuba's impoverished eastern tip.

"We are recovering knowledge that was forgotten, knowledge that my parents and grandparents had," said Fuentes, 51. "A lot of people had knowledge but lived and died without knowing its Indian origin."

Experts say Taino influences are everywhere.

The palm-thatched huts common in the region are similar to those built centuries ago by the indigenous group. Some farmers till the soil using a long, sharpened pole known to the Taino as a coa.

Fuentes said he uses a coa to remove old plantain trees and dig latrines, while harvesting beans, sweet potatoes and other crops according to the four lunar phases - a belief system of indigenous origin.

Some coastal residents fish with small nets in the Taino style and crabs are trapped using a crude, box-shaped device that has changed little over the centuries, experts say.

Although the Taino language, Arawak, has all but died in Cuba, hundreds of indigenous words are peppered throughout the local Spanish. Many of the names of the island's most well-known places - from Havana to Camaguey to Baracoa - come from the Arawak language.

"The Taino culture permeates the culture of Cuba in a fundamental way," explained Jose Barreiro, a Cuban-American scholar of Taino history. "It's the base culture of the country along with Spanish and African influences."

Experts say the Taino migrated north from South America's Amazon basin centuries ago, populating much of what is now Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and Cuba.

The Taino arrived in Cuba about 300 years before Columbus and eventually numbered in the hundreds of thousands.

Organized in villages under the authority of caciques or chiefs, the Taino cultivated beans, yucca, corn and other crops, along with something they called cohiba, or tobacco.

They hunted turtles, snakes, iguanas and a giant rodent called a jutia, while also adhering to a complex set of spiritual beliefs whose primary deity, Yucahuguama, represented agriculture and the ocean.

Roberto Ordunez, an anthropologist and director of the Taino museum in Baracoa, a picturesque colonial town of 50,000, said Columbus described a large, thriving agricultural community.

"I climbed up a mountain and found the flat lands planted with many things," Ordunez said Columbus observed in his journal in 1492. "It was a pleasure to see it and in the middle of it was a large population."

Although the Taino left no large monuments, they built canals for channeling water, caves for storing food during drought and a network of stone footpaths for travel and to escape their enemies, a raiding tribe known as the Carib.

But the Taino had no chance against the Spanish, who brought malaria, smallpox and other deadly diseases, along with modern weapons.

Still, some put up a fight.

An indigenous leader named Hatuey traveled from the island of Hispaniola to Baracoa to warn the Tainos about the conquistadores. He was captured, refused to convert to Christianity and was burned at the stake.

Hatuey remains a revered figure in Cuba, where his story is among the first lessons taught to schoolchildren.

"Hatuey is considered the first rebel in America because he was the first to understand the abuses of the colonialists and rebel against them," explained Noel Cautin, a guide at the Taino museum.

A second indigenous leader, Guama, launched hit-and-run attacks against the conquistadores for a decade before he was killed, perhaps by his own brother, in 1532. By then, the Taino numbered only a few thousand, a figure that continued to plummet. Historians in the 19th century declared there were no indigenous left on the island.

"Those who remained were in remote areas and the historians were primarily in the cities," Barriero said. "The Taino also had adopted Spanish technology and language."

Barriero and others say that not a single Taino community remains intact, though the group's culture is best preserved in La Caridad de los Indios and a handful of other remote villages in the mountains southwest of Baracoa.

In a sign of growing international recognition, the Smithsonian Institution last year returned bone fragments from seven Taino Indians to the La Caridad community for a sacred reburial.

The human remains along with thousands of indigenous artifacts were taken almost a century ago by American archaeologist Mark Harrington and later fell into the possession of the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian.

Another source of pride is Baracoa's modest Taino museum, which opened last year in a hillside cave and displays pendants, necklaces and other pre-Columbian artifacts made of shells and other materials.

Fuentes has visited the museum twice.

"I felt pride because I hadn't see these things before and because I'm part of this culture," he said.

Labels:

Alejandro Hartmann,

Arawak,

Baracoa,

beans,

corn,

Cuba,

Guajiro. Jose Barriero,

Guama,

Haiti,

Hatuey,

Jose Barreiro,

Puerto Rico,

Roberto Ordunez,

Taino,

the Dominican Republic,

yuca

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)