BY GARY MARX

Chicago Tribune

YARA, Cuba - (KRT) - In a sweltering coastal settlement, Alejandro Hartmann pulled out a spiral notebook and jotted notes as a local peasant described his family's ties to a long forgotten indigenous group that is witnessing a modest resurgence.

"What is the name of your mother and father?" Hartmann asked Julio Fuentes, a wisp of a man parked on a wooden bench. "Where do they live? How old are they?"

Hartmann fired off a dozen more questions as part of his effort to complete the first census of the descendants of the Taino Indians, an indigenous group that once thrived in this remote region of eastern Cuba and later were thought to be extinct.

"Julio is a mixture of Spanish and Indian like many people," explained Hartmann, a historian and Taino expert. "I want to eliminate the myth once and for all that the Indians were extinguished in Cuba."

For years, anthropologists widely believed this island's once-powerful Taino Indians were exterminated shortly after Christopher Columbus sailed into a pristine bay and walked the steep, thickly forested terrain more than 500 years ago.

The explorer spent only a week in the area in 1492 but described the Taino as gentle, hard-working people growing crops and navigating the crystalline waters in huge dug-out canoes.

But, in a familiar story throughout the Americas, war and disease decimated the Taino, whose sense of identity was further razed over the centuries by racism and by generations of intermixing with whites, blacks and others who settled here.

Today, it's difficult to differentiate Taino descendents from the average Cuban peasant, or guajiro, as they are called.

Yet, Hartmann and a group of experts continue to press ahead, rewriting the tale of the Taino's demise in an effort to set the historical record straight and foster recognition among the island's 11 million residents of the group's contribution to Cuban life.

With a new museum, academic conferences and other projects, they also are trying to nurture a nascent sense of identity among the hundreds - perhaps thousands - of Taino descendents who are scattered along Cuba's impoverished eastern tip.

"We are recovering knowledge that was forgotten, knowledge that my parents and grandparents had," said Fuentes, 51. "A lot of people had knowledge but lived and died without knowing its Indian origin."

Experts say Taino influences are everywhere.

The palm-thatched huts common in the region are similar to those built centuries ago by the indigenous group. Some farmers till the soil using a long, sharpened pole known to the Taino as a coa.

Fuentes said he uses a coa to remove old plantain trees and dig latrines, while harvesting beans, sweet potatoes and other crops according to the four lunar phases - a belief system of indigenous origin.

Some coastal residents fish with small nets in the Taino style and crabs are trapped using a crude, box-shaped device that has changed little over the centuries, experts say.

Although the Taino language, Arawak, has all but died in Cuba, hundreds of indigenous words are peppered throughout the local Spanish. Many of the names of the island's most well-known places - from Havana to Camaguey to Baracoa - come from the Arawak language.

"The Taino culture permeates the culture of Cuba in a fundamental way," explained Jose Barreiro, a Cuban-American scholar of Taino history. "It's the base culture of the country along with Spanish and African influences."

Experts say the Taino migrated north from South America's Amazon basin centuries ago, populating much of what is now Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and Cuba.

The Taino arrived in Cuba about 300 years before Columbus and eventually numbered in the hundreds of thousands.

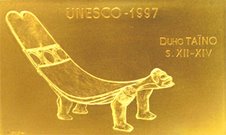

Organized in villages under the authority of caciques or chiefs, the Taino cultivated beans, yucca, corn and other crops, along with something they called cohiba, or tobacco.

They hunted turtles, snakes, iguanas and a giant rodent called a jutia, while also adhering to a complex set of spiritual beliefs whose primary deity, Yucahuguama, represented agriculture and the ocean.

Roberto Ordunez, an anthropologist and director of the Taino museum in Baracoa, a picturesque colonial town of 50,000, said Columbus described a large, thriving agricultural community.

"I climbed up a mountain and found the flat lands planted with many things," Ordunez said Columbus observed in his journal in 1492. "It was a pleasure to see it and in the middle of it was a large population."

Although the Taino left no large monuments, they built canals for channeling water, caves for storing food during drought and a network of stone footpaths for travel and to escape their enemies, a raiding tribe known as the Carib.

But the Taino had no chance against the Spanish, who brought malaria, smallpox and other deadly diseases, along with modern weapons.

Still, some put up a fight.

An indigenous leader named Hatuey traveled from the island of Hispaniola to Baracoa to warn the Tainos about the conquistadores. He was captured, refused to convert to Christianity and was burned at the stake.

Hatuey remains a revered figure in Cuba, where his story is among the first lessons taught to schoolchildren.

"Hatuey is considered the first rebel in America because he was the first to understand the abuses of the colonialists and rebel against them," explained Noel Cautin, a guide at the Taino museum.

A second indigenous leader, Guama, launched hit-and-run attacks against the conquistadores for a decade before he was killed, perhaps by his own brother, in 1532. By then, the Taino numbered only a few thousand, a figure that continued to plummet. Historians in the 19th century declared there were no indigenous left on the island.

"Those who remained were in remote areas and the historians were primarily in the cities," Barriero said. "The Taino also had adopted Spanish technology and language."

Barriero and others say that not a single Taino community remains intact, though the group's culture is best preserved in La Caridad de los Indios and a handful of other remote villages in the mountains southwest of Baracoa.

In a sign of growing international recognition, the Smithsonian Institution last year returned bone fragments from seven Taino Indians to the La Caridad community for a sacred reburial.

The human remains along with thousands of indigenous artifacts were taken almost a century ago by American archaeologist Mark Harrington and later fell into the possession of the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian.

Another source of pride is Baracoa's modest Taino museum, which opened last year in a hillside cave and displays pendants, necklaces and other pre-Columbian artifacts made of shells and other materials.

Fuentes has visited the museum twice.

"I felt pride because I hadn't see these things before and because I'm part of this culture," he said.

roughout the Western Hemisphere and the Pacific Islands.

roughout the Western Hemisphere and the Pacific Islands. roughout the Western Hemisphere and the Pacific Islands.

roughout the Western Hemisphere and the Pacific Islands.